Just north of the Alps, on the border between Germany and Switzerland, lies beautiful Lake Constance. And on the northwest shore of the lake is the lovely small city of Constance, Germany.

Constance is well worth a visit. A lot of German cities have rather bland or unattractive centers, thanks to the American and British air forces. But Constance escaped these attentions entirely, because the Allies didn’t want to risk any bombs landing in neutral Switzerland. So Constance has an unusually intact Old Town with lots of interesting old buildings, some going right back to medieval times.

Constance also has this::quality(80)/images.vogel.de/vogelonline/bdb/1272600/1272674/original.jpg)

A nine meter tall, 18 ton statue of a medieval sex worker. She’s down at the harbor, on the lake. She rotates once every four minutes. Her name is Imperia.

You may reasonably ask, what? And part of the answer is, she’s memorializing the Council of Constance, the great political-religious council that happened here 600-some years ago, from 1414 to 1417. And you may ask again, what?

I’ll try to explain.

Constance

Lake Constance gets its modern name from the city of Constance. And the city of Constance is named after Constantius, a fourth century Roman emperor.

[probably this guy, though it might have been his grandson. it was the 4th century, stuff got confused.]

Back in the first century AD, the Romans pushed up through the Alps into what’s now southern Germany. They brought peace to the region via their traditional mix of mass murder, ethnic cleansing, and forced Romanization. They seem to have built a bridge at Constance — the lake tapers down to a narrow neck there. And credit where it’s due: the Romans loved nothing better than building transport infrastructure. Bridge going north, good Roman roads going south, inevitably a town sprang up. Later, in the 4th century when the Empire was turtling up against the ever more aggressive barbarians, the trading town built walls. It became a border fortress, and got a new Imperial name.

(You have to work a bit to find corners of Europe that haven’t been touched by someone’s empire. Roman, Frankish, Byzantine, Holy Roman, Ottoman, Spanish, French, Russian, British, German… ruins and roads, castles and place names, borders and battlefields. The continent is pock-marked with them like acne scars.)

The Romans eventually departed, but the bridge and the town seem to have survived. Certainly both were still there a thousand years later, when the Catholic Church convened a General Council there in 1414.

So is Imperia about the Roman Empire, then?

No, not at all. Well… not directly.

Three Popes, One Council

“And if a man consider the original of this great ecclesiastical dominion, he will easily perceive that the papacy is no other than the ghost of the deceased Roman Empire, sitting crowned upon the grave thereof: for so did the papacy start up on a sudden out of the ruins of that heathen power.” — Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan

For a while, back in the 14th century, there were two rival Popes. Each had his own Papal court and hierarchy, each was doing all sorts of Papal things — collecting religious dues, appointing Bishops and Cardinals, excommunicating heretics — and each was recognized by about half of Europe. This was generally agreed to be a bad situation! So there were several attempts to fix this problem. They all failed, and one went so spectacularly wrong that it produced a third Pope, recognized by another couple of European countries.

At this point pretty much everyone agreed that something drastic had to be done. So a General Council of the Church was called, with implicit power to sit in judgment on all three rival Popes. Italy was problematic for a bunch of reasons, France was in the middle of the Hundred Years War —

[Branagh or Olivier? discuss.]

— so after some discussion it was decided to convene the Council in the small neutral city of Constance, which if nothing else was centrally located.

In Conference Decided

“A conference is a gathering of people who singly can do nothing but together can decide that nothing can be done.” — Fred Allen

The Council of Constance is just so darn interesting.

I’ll try not to chase too many rabbits, but here’s a thought. In the early 15th century Europe was, in terms of global civilization, a backwater. The Chinese were more technologically advanced, India was richer. Asia was full of cities that were larger, cleaner, safer, and better designed than Europe’s grubby little burgs. Heck, the contemporary Aztecs had a capital at Tenochtitlan that was bigger and nicer than anything in Europe, and those guys were barely out of the Stone Age.

Europe had nothing that the rest of the world particularly wanted to buy, which meant that Europe had been running a trade deficit for literally centuries. (This would lead to a serious economic crisis later in the century, as the continent nearly ran out of gold and silver.) Militarily, Europeans had been losing battles and wars to non-Europeans for a while, and this would continue for some time. In particular, the Ottomans had just embarked on a long career of kicking Europe’s ass. Within a century, a huge chunk of the continent would be Ottoman provinces or tributaries.

And yet. Somewhere along the line, Europe went from “D-tier also-ran kind of lame civilization” to “planetary apex predator”.

Why? Why Europe?

Some of the world’s smartest people have spent lifetimes of scholarship trying to answer that question. Not for a moment will I imagine I can add anything useful to that great debate. But here’s an offhand thought: there’s a short list of things that are, historically, unique or nearly unique to Europe. One of those things? International conferences.

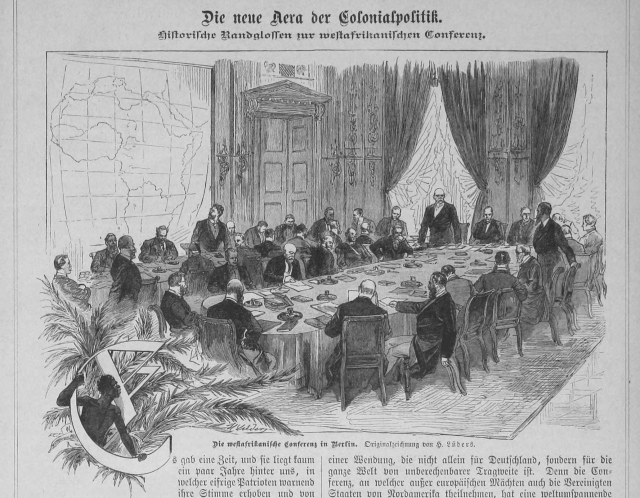

[it doesn’t get much more European than this.]

This is probably because international conferences started as a particularly Christian thing. The early Church was spread broadly but thinly across a politically united Roman Empire that had, for a premodern state, unusually excellent transport links. (See earlier comment re: Romans and transport infrastructure.) So it made sense to periodically come together: to keep doctrine and practice consistent, to resolve leadership disputes, and just generally to settle questions that couldn’t be worked out locally. The great-grandfather of them all was the Council of Nicaea, back in 325 AD, which gave us the Nicene Creed.

[BEGOTTEN NOT MADE HERETIC iykyk]

And there were lots more Councils, all through late Antiquity and the Middle Ages: Chalcedon, Constantinople, Lateran, Lyons.

But there’s a second line of mostly secular conferences called by Europeans to resolve international disputes: most typically to end a war, but often with a sidebar of “and let’s try to set up some sort of international order”. And you can argue with a straight face that the Council of Constance is the takeoff point for this second line.

Because Constance was a Church council, yes. But it was also political in a way that previous medieval Councils hadn’t been. It was attended by kings and dukes and counts, lawyers and professors and representatives of Imperial Free Cities — in fact, the lay attendees may have outnumbered the clerics. It relied on the Emperor Sigismund to provide security and enforcement. Its decisions required buy-in from the secular authorities. Voting at the council was done by “nations” — groups of Churchmen, but sorted geographically by region within Europe. And while Church reform and heresy were on the agenda, the overriding imperative was straight-up power politics: to resolve the Papal schism and settle the Church’s internal government.

So on one hand, Constance was just another in that long line of Church councils from Nicaea to Vatican II (1962-65). But at the same time, it was arguably the first great multilateral peace conference. Lodi, Westphalia, Vienna, Versailles, Yalta: Europeans have been holding these conferences for a long time. There’s a direct line from Constance to the G-20.

— No, I’m not claiming that international conferences are what made Europe special. I’m just noting that these secular peace-and-international-order councils really get going in the 15th century, right around the time that Europe begins its slow ascent out of mediocrity. Almost certainly a coincidence! Still: interesting.

Deliverables

So the Council of Constance had three declared goals, plus one goal that was undeclared but universally recognized.

The declared goals were:

1) Fix the whole three Popes thing.

2) Deal with heresy. Specifically, deal with Jan Hus, who was the beta version of Martin Luther, and his followers. The Hussites had basically taken over one European country already, and were threatening to spread.

3) Reform the Church, which everyone agreed was spectacularly corrupt, and doing a pretty terrible job of providing spiritual guidance and moral leadership to Catholic Europe. (This was cross-wired with (2) because the Hussites were claiming to be, not heretics, but reformers.)

The undeclared goal was

4) By asserting the superiority of a Church Council over Popes, convert the Catholic Church from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy.

Nobody was publicly saying this was the plan, but this was totally the plan. There had been a bunch of bad Popes already. It was clear that giving that much power to anyone was a dubious idea to begin with, and that this was made worse by a selection process that favored ruthless conniving corrupt SOBs.

Getting rid of the Papacy was unthinkable, of course. But regular Church Councils to keep the Popes in check? That seemed entirely doable.

Key Performance Indicators

They succeeded at (1) and failed at the other three.

They did burn poor Jan Hus. It’s a sad story and I won’t go into the details. TLDR, they burned him, but the Hussites took over Bohemia anyway — the modern Czech Republic, more or less — and stayed in power there for over a century. The secular rulers around them did manage to contain the Hussite heresy and keep it from spreading, but that wasn’t because of anything the Council did.

But the really consequential failures were that they utterly failed to reform the Church and they didn’t curb the powers of the Papacy. The Church would remain horrifically corrupt, and the Popes would remain autocratic — and all too often greedy, cruel, and completely uninterested in providing spiritual or moral leadership.

It would take nearly another century for these particular chickens to come home. But the eventual, inevitable result was the Protestant Reformation.

[hammer time]

By failing to fix the system, the attendees of the Council guaranteed that the system would eventually explode.

But, really, how could they do otherwise? Cardinals and bishops and abbots, counts and dukes and kings, priests and professors… they were all products of the system, and they were all benefiting from it.

Somewhere, Imperia is smiling. We’ll get back to Imperia.

One fled, one dead, one sleeping in a golden bed

So what happened to those three Popes, anyway?

Well: John, the Neapolitan Pope, was a pretty sketchy character even by the low standards of late medieval Popes. Among other things — many, many other things — he was plausibly suspected of having poisoned his predecessor. So the Council offered him a deal: resign, and we won’t open an investigation into these accusations. Since an investigation would lead to a trial, and a trial would lead to a conviction, Pope John agreed and stepped down.

But then! John slipped out of Constance — disguised as a postman, some say. He fled to the castle of a friendly noble, un-resigned, and declared the Council dissolved.

The Council wasn’t having it. The Holy Roman (German) Emperor summoned an army to besiege the castle. John fled again, but the Emperor’s forces followed. Eventually he was caught and dragged back to Constance, where they did put him on trial, and convicted him too. He spent several years in comfortable but secure confinement. He was allowed out once it was clear that he would behave himself, i.e. not try to be Pope any more.

Now, one of John’s few accomplishments as Pope was choosing the Medici of Florence as his bankers. Did you ever wonder why the Medici were such a big deal? It’s because they were the bankers for the Papacy for almost a century. Immense sums of money flowed into Rome from all over Europe. All of it passed through Medici hands at some point, and of course the bankers took their cut.

And, credit to the Medici, they used at least some of that money to become some of the greatest patrons of art that the world has ever known. Michelangelo, Botticelli, the Duomo, Donatello, the Sistine Chapel… all that happened because of bad Pope John.

[“Award of a Sole Source Contract for Financial Services”, fresco, c. 1509]

When the disgraced ex-Pope eventually died, the reigning Pope didn’t want to give him a burial in Rome. So the grateful Medici whisked John’s body off to Florence, where they gave him a nine-day funeral. Then they built him a nice little tomb. It was eight meters tall, marble and gilt, with Corinthian columns and a bronze effigy — you know, the usual — designed by Medici client artists Donatello and Michelozzo. It’s still there in Florence today.

[phrases rarely found together: “Medici” and “tasteful understatement”]

Gregory, the Venetian Pope? He cut a deal. He agreed to resign if (1) the Council subsequently acknowledged that he had been the One True Pope all along, so that his rivals were declared schismatic antipopes, and also (2) he got a unique one-time title of “Second Most Important And Holy Guy In The Church, After The Pope”. The Council decided this was cheap at the price, and agreed.

So Gregory is still counted by the Catholic Church as an official Pope. (Which means he was the last official Pope to resign the office until Benedict XVI’s abdication in 2013, five hundred and ninety-seven years later.)

[he even got to keep the hat]

Benedict, the Spanish Pope? He refused to resign. But the Council went to work on the remaining countries and monarchs who were supporting him, and talked them around. So Benedict ended up abandoned by most of his supporters. He died a few years later, mule-stubborn to the end, isolated and mostly ignored.

That time they elected the Pope in a shopping mall

Once the Council had eliminated or sidelined the three Popes, they needed to choose a new one. For this, they used a unique, one-time-only system of voting. Council attendees gathered into geographic “Nations”, each nation picked six guys to represent them, those six guys cast one vote. This was an attempt to put a new, Council-based system of Pope selection in place, since the existing College of Cardinals process kept throwing up Popes who were scheming evil bastards.

It didn’t take. The next Papal election took place when there was no Council, so they went right back to the College of Cardinals.

[and they’ve kept it ever since]

But they also had the problem of where to hold the election. Because traditionally, Papal electors are isolated, cut off from outside influences until they decide. So they needed a building that was large, but that could be sealed off, but also handed over to the electors for some indefinite period of time. As it turned out, medieval Constance had exactly one building that fit the requirements: the town Kaufhaus.

Today the word “Kaufhaus” gets translated as “department store”. But the Constance Kaufhaus was a combination warehouse and retail center. Foreign merchants kept and sold premium goods there. It was a big building full of little shops selling luxury items. Literally, a high-end shopping mall.

Still, needs must. And credit to the electors: they managed to reach a consensus and elect a Pope who was, if not brilliant, at least not an incompetent, a criminal, or a monster. Pope Martin V would rule for 13 years and while he wouldn’t do much that was memorable, neither would he poison his enemies, appoint a bunch of nephews and bastard sons to high office, run the Church into bankruptcy, or otherwise disgrace the office.

Of course, this goes to a deep structural problem. The Council chose a kindly mediocrity because they were afraid that a strong Pope would claw power back from Councils. (Which is exactly what happened, a Pope or two later.) But the Church desperately needed reform, which a kindly mediocrity couldn’t possibly deliver.

Also, the College of Cardinals absolutely hated the idea of anyone else being involved in electing the Pope. Partly this was a status issue. Partly it was about ambition — most Popes came out of the College, after all. (Still true.) But most of all, it was about cold hard cash. Would-be Popes were often willing to pay immense bribes in order to buy votes. Kings and Dukes would throw in more bribes to support or oppose a particular candidate. Banks and wealthy families would coolly lend money to finance these bribes, since backing a winning Pope could mean an instant flow of massive wealth.

This is, of course, how the Medici became the Papal bankers. It was they who funded the election of bad Pope John in the first place.

[Allegory of a Papal Election, c. 1480. the winged figures represent the Medici, scattering flowers (money) as they blow the candidate to the shores of success. the handmaiden (the Church) is about to clothe her in a robe decorated with flowers (even more money). the candidate gazes into the middle distance, seemingly unaware.]

So reforming the electoral process would not only have been a hit to the Cardinals’ status, it would also have drastically curtailed their future income. It’s no surprise that they weren’t enthusiastic about the new system, and abandoned it as soon as they could.

Somewhere, Imperia is still smiling. We’ll get back to Imperia.

Everybody goes home

The Council wrapped up in 1418. Joan of Arc would have been in first grade, if medieval French peasant girls went to first grade, which they didn’t. She was about 10 years away from starting her brief incredible career as the savior of France. Johannes Gutenberg was a freshman at the University of Erfurt. He was about twenty years away from inventing the printing press. Over in England, a handsome young Welshman named Owen Tudor was hanging around the court of King Henry V. In a few years, King Henry would die of dysentery. His widowed Queen would marry handsome Owen. Their grandson would be the first Tudor king of England, and their descendants are sitting on the British throne today.

Jan van Eyck was in his twenties, just getting started on his career as a painter.

[weird mirrors were already a thing]

And down in Portugal — a kingdom small and obscure even by medieval European standards, out on the far edge of the continent — Prince Henry the Navigator was forming an ambitious plan. Portugal, like the rest of Europe, was running out of gold. But there was gold down in Africa… somewhere. It came north regularly, after all, in caravans across the Sahara. The trade was controlled by Islamic middlemen, who took a hefty cut.

But what if Portuguese ships could work their way down along the African coast? They might find the source of the gold… and who knows what else?

[just getting started]

And that’s the story of the Council of Constance.

But wait, you ask. What about Imperia?

Yes, well… this post got a little out of hand. But Imperia is not forgotten! Modern Constance has a nine meter, 18 ton concrete statue of a medieval sex worker that rotates every four minutes, and there’s a reason for that. We’ll get to her story shortly.

Because she is most certainly still smiling.