Aliens must go

Papers and passports

Inspection of identity

Stamp of approval

Proof of residency

Overstayed welcome

Fairweather friends

Fiasco

Exigency

Scapegoats

Contingency

Indefinite leave to remain

There's a price to be paid

Fraught deadlines

Tight timetable

Hasty evacuations

Explicit threats

Swift deportation

Fractured boundaries

Unkind labels

Verbal taunts

Herd of illegals

Circling touts

Overnight precarity

Status in doubt

Expulsion orders

Border crossings

Crowded ports

Land checkpoints

Dispersed families

Rushed upheaval

Overstuffed bags

Hurry

Tension, loss

Worry

Official decisions

Informal penalties

Enforcement actions

Emboldened gatekeepers

Entry permits

Mournful exits

Brethren

Neighbors

Rivals

Strangers

State of emergency

Failure of diplomacy

Ancestral memory

Histories of dislocation

Politics of closures

Season of migration

Internally displaced

Traditional evacuees

Modern travelers

Sudden refugees

Aliens must go, a playlist

A soundtrack for this note (spotify version)

- Gone baby, don't be long by Erykah Badu

- Uptown by Raphael Saadiq

The plaintive refrain and coda is the sound of wist: "I'm leaving this town" - I gotta get away by Gloria Barnes

- Pack'd my bags by Rufus ft Chaka Khan

- Leavin' by Tony Toni Tone

- I gotta go by Lizz Fields

- Don't talk to strangers by Prince

- Gone baby, don't be long by José James

- Don't talk to strangers by Chaka Khan

See previously Bags and Stamps (Ghana must go) and Expulsion orders

...

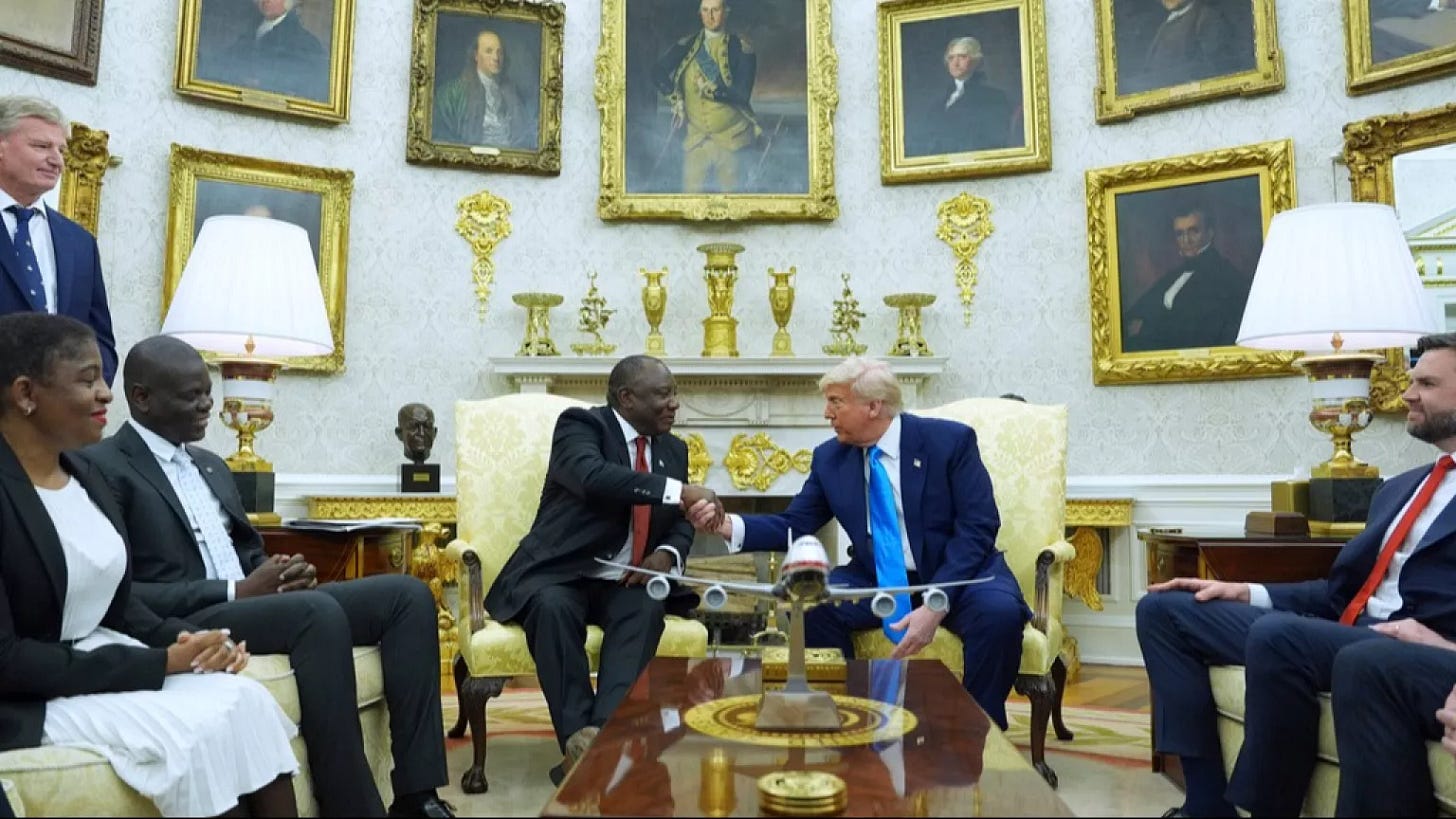

Postscript (June 3, 2025)

My current publishing schedule means that what you read above today was written three years ago (Indeed, if I don't pick up the pace, the trifle I wrote today will only see the light in 2038, 12 1/2 years from now). That being said, I am struck that the above musings on displacement, forced and otherwise, that I wrote in 2022 still seem timely.

I was then in the process of digitizing the Talking Drums archive and taking in the reverberations of arbitrariness and the reign of strongmen in khaki in what I read in those pages. The ripple effects continue over the surface of our regional politics.

My friend Senam had just published her dissertation and was sharing some of the stories that she'd unearthed in her excavation of this, our signal topic. Ghana must go has a very tangible legacy beyond Nigeria and Ghana. It is a living history, disclosed often by artful omission and subject to the opacity of our elders. It a family history and, in its sweep, marks its bearers.

More recently, I've been thinking about the exodus from Sudan and what that country has suffered in the past two years, the reign of locusts, if you will. You don't hear much about the strain on the surrounding countries and the fodder for resentment that any old demagogue could harness if they chose to do their worst. I've been thinking of the smaller but no less disruptive waves in the Sahel region where many leaders are indeed inclined to do their worst for fear of losing their positions. Displacement seems to be the rule and many of our neighbors' houses are on fire.

This is a time of brutes.

And here, again, I welcome the US to the Third World. The Stephen Miller incited and Trump led assault on everything is hitting many near and dear to me. Things have long moved far beyond rhetoric. Livelihoods and personal safety are affected, even moreso than usual for those darker than blue. Unspoken threats now explicitly verbalized. And horizons have contracted. Many now adopt a fetal pose to shield from the incoming blows heeding the warning: protect yourselves at all times.

This is a time of precarity.

And exhaustion. Take, say, immigration for example. Many of my cousins are on student or other immigrant visas in the US, and are currently weighing the calculus of just being themselves versus adopting a studied pose of neutrality and normalcy.

No sudden moves is the refrain, don't become a target etc. It looms, that culture of silence. It's present, the retreat to that mask of civility that we wear all too well.

This is a time of erasures.

People disappear, sometimes literally pulled off the streets, bodies are snatched with glee. But worse is the eclipse of the soul. Pieces of identity are being erased. The spark and joie de vivre in many is being extinguished, curtailed by cruelty and disembodied by vindictiveness. I can't recognize so many folk.

Sidenote: one of my cousins was recently accepted by Harvard, all his hard work paying off. After the initial celebrations, however, everyone in the family has been holding their breath as we watch that institution and others being targeted. The saving grace is that he was born in the USA and so is somewhat shielded from the trials of non-citizens. (I'm still somewhat curious about whether the currenly stymied attack on birthright citizenship would notionally affect him, or if that strange interpretation would only affect births going forward). I don't envy him. He gets to wear multiple mantles as a living embodiment of Stephen Miller's worst fears, a foreign student but also an American-African and that's before he even opens his mouth. I really don't envy him. What paradise have we lost?

Anyway... Perhaps, this is all background noise, and, as I'm often reminded, the virus sets the timeline. The ongoing pandemic can make all this turmoil in the world moot, a sideshow at best, in very short order.

Aliens must go. I too will make my accommodations. I continue to focus on small things and move to my own tune. The present collection of toli, being doled out every week, bears a title that is all I aspire to: A Comfortable Unease.

File under: Ghana, Nigeria, culture, immigration, displacement, exile, memory, Africa, history, politics, dictator, coup, loss, observation, perception, refugee, Things Fall Apart, Ghana must go, poetry, toli

Writing log: September 6, 2022