I give you the archive of

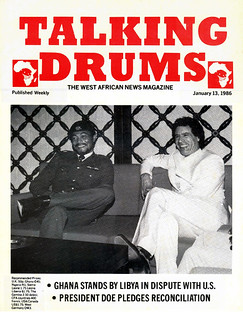

Talking Drums, the West African news magazine, a window into the continent's life from 1983 to 1986.

https://talkingdrumsmagazine.com

Head on over to the site to browse through a few issues and take in a slice of those four years and let me know what you think. As always, I have a few notes...

The Talking Drums Story

We need leaders, We need responsible citizens sufficiently dissatisfied with things as they are and impatient enough to do something about it, intelligently, quietly, wisely. We need critics too, for dissenting is a serious, worthy and honest pursuit.

- Elizabeth Ohene, Ben Mensah, and Kofi Akumanyi in the inaugural issue of Talking Drums (September 12, 1983)

Some forty years ago, three Ghanaian journalists, found themselves in exile in London in the aftermath of the Rawlings-Tsikata coup of December 31, 1981. They had been among the first wave of graduates of the school of journalism at the University of Ghana, Legon and had gone on to work the Daily Graphic in the early 70s. Starting at the very ground floor of the paper, they had progressed to become senior editors, bringing the newspaper to the peak of its influence in the country.

The Graphic had put the Limann regime on notice and a vibrant discussion was taking place in the country - it seemed quite clear that democratic change would be coming to the third republic. The coup put an end to the country's fledgling experiment with normalcy and its aftermath was bloody and full of peril. The junta were hell-bent on a "revolution" and for safety, it was flight into exile for them and their families.

They likely expected a return to civilian rule within short order but they also intimately knew the cast of characters involved in the coup. Their worst fears were realized as they saw them do their worst. The PNDC leaders encouraged and visited stochastic violence on Ghana, throwing the country into upheaval with all manner of political and economic turmoil. The murder of the judges probably crystalized things, but even before that awful event, news became scarce about what was going on in Ghana. The search for facts about life in Ghana that was their very lifeblood had been summarily curtailed - and not just for them but for everyone.

What was also galling was the coverage of African affairs they encountered from without. West Africa magazine parroted the official line and the media of the erstwhile francophone countries were suitably neutered. And the less said about Western media sources the better. The professional stenographers, say Victoria Brittain in the Guardian, were in full flow, reputation laundering and devoted all their newsprint to lauding the mostly military regimes that were running rampant all over the continent.

And so they wrote their way out of things. There were letters to the editor, there were guest columns and such, they pestered every media outlet that they could. Thoroughly dissatisfied as the months turned to a year, they simply decided that there was a space for a news magazine that presented an alternative viewpoint. And so they embarked on the grand experiment that was Talking Drums.

The ambition was to create a formidable newsroom, to summon accurate coverage of a continent in bad need of news. To conjure a comprehensive record in a time when coverage of Africa was minimal at best, and misinformed in the main. Talking Drums would be positioned as a critical antidote for a region in upheaval.

The excuse that African soldiers traditionally give for throwing elected governments out of power is that they are corrupt and innefficient and even though the soldiers themselves regularly turn out to be as corrupt and chaotic as the civilians they have overthrown, the fact that corruption does exist when the guns far first taken usually means that the promises made by the soldiers sound like music to the ears of the tired and oppressed peoples

- Editorial in the inaugural issue of Talking Drums

The editorial line, such as it was, was skeptical and often scathing. The core of the magazine however was old fashioned journalism: the search for facts and for the story. Reporting in Talking Drums was about looking at what those regimes of strongmen actually did, what their policies on the ground were leading to, pointing out the likely consequences in advance, the obvious pitfalls and the waste and avoidable suffering that would inevitably ensue.

It wasn't quite naming and shaming rogues - for that would imply that shame would have an impact, it was the journalistic impulse at work - telling the story, making sense of the often chaotic raw material and outlining the narrative strands and the motivations behind them.

From that core, they were joined by others and built a newsroom reporting from the continent. They added coverage on all the things one would expect, from politics to economics, science, sports, music and arts.

A few months after they started, the Nigerian military, led by Buhari, took over in a coup on 31st December 1983 again curtailing democracy. The need for an alternative viewpoint became even more urgent. Nigeria had been a relative beacon for the continent with a civilian government that had even conducted elections whose outcome was not disputed in the country. Instead, the men in khaki seemed set on putting their stamp on the country as elsewhere.

Musa Ibrahim would join the Talking Drums from Nigeria and, with his pseudonymous column, Whispering Drums, would lead their coverage on Nigeria. Others would join the newsroom in short order and Talking Drums would start to be the an effective outlet for the kind of news they envisioned. And the audience responded to the challenge, the letters page became quite active and they garnered the informed readers they expected. Some readers even became contributors heeding to the mantra was repeated in every issue.

Don't whisper in frustration. Get if off your chest now! Write to Talking Drums.

The archive is

now available. Just under 100 issues are there to enable you to find out what this was all about. Let me know what you think or if there any broken links and such. Enjoy.

An Oral History of Talking Drums

I moderated a session with some of the principals a few weeks ago; I encourage you to read the linked transcript. Unfortunately I failed to record the video feed but the words resonate

I'll be following up in Part 2 which will I hope will feature Musa Ibrahim giving his perspective on

Whispering Drums with Maigani, his pseudonymous column that covered Nigeria. I also hope to engage with Tina Akumanyi, the widow of the late Kofi Akumanyi, on his inspired column

A Touch of Nokoko that was a constant in the life of the magazine.

I expect too that all those that were part of the Talking Drums story will undoubtedly be writing their own pieces - they can't help writing, and I'll be sure to update the web site as they do.

The Newsroom

A brief guide to the features of Talking Drums and some of those who produced it every week out of amall offices in Madhav House in northwest London.

- Elizabeth Ohene was Editor of Talking Drums. Previously she had been Editor of the Daily Graphic before the 31st December 1981 forced her into exile. After Talking Drums she would join the BBC African Service. Although mostly responsible for editorials and opinion columns, I can vouch that on some occasions she penned a great amount in other areas of the reporting; our correspondent was very busy.

- A Touch of Nokoko. Kofi Akumanyi's delightful column cast his roving eye on every aspect of life. "The column that pulls your leg" was a good description of what he was going for. It was full of the twists and turns, sharp observations and dancing with the absurd. He was a former Features Editor of the Daily Graphic. Sad to say, he passed away in 2009 of cancer. He was 64. His voice is sorely missed.

- Ben Mensah was columnist and News Editor of Talking Drums. He was a former News Editor of the Daily Graphic. He covered the nitty-gritty of finance, economics and politics. If you want to know about the trials and tribulations of operating a business in West Africa during this time, you couldn't find a better source.

- Whispering Drums by Maigani. Musa Ibrahim decided to use a pseudonym for his reporting from Nigeria. On many occasions his weekly insights were the best ways to understand what was going on in the country, the various factions that were making hay out of the country's resources while claiming indiscipline. His witty and acerbic provocations roused the military government who were not used to being so plainly exposed. The feared heads of the National Security Organisation (NSO) and other security men would submit rejoinders to his work, which even provoked a few lawsuits. Suffice to say that he touched a nerve.

- Science and Technology by Poku Adaa

Tropical Sciences correspondent filed numerous articles on industry and the ups and downs of development

- People, Places, Things

The tidbits or almanac pages were very important to the magazine, compiling a weekly view of the news on a country-by-country basis. In many ways this was the meat of the reporting and many readers would hang on the revealed details.

- What The Papers Say

A periodic look at the media on the continent. Oftentimes African newspapers were serving as government mouthpieces but occasionally one could find journalists trying to assert their independence - this would typically be on foreign affairs. Sometimes they even strike a nerve, you can get a sense of why mild mannered The Catholic Standard, of all papers, came to be banned by the PNDC.

- A Stranger's London

Billed as watching the natives in their natural habitat, in later issues it was retitled A Stranger's Britain.

- Sports, Music and Arts.

Ebo Quansah, Kwabena Asamoah and Staccato were the main correspondents turning in acute reporting on sports, reviews of African music concerts. The cultural scene was quite vibrant many artists were turning in prime performances despite their troubles at home (see Fela for example who would face jail and harrassment from the military regime. For what it's worth there's a Talking Drums playlist, a selection of some of the music reviewed in these pages.

- Short Stories

From the beginning the magazine solicited and readers contributed short stories. Some were very well executed including a few fascinating stories from Hassan Ali Ganda. I was surprised by the variety of styles and topics.

I've long bemoaned that our writers have not really tackled the story of the Rawlings years so color me corrected as I read several short stories covering the judges's murders and Ghana must go. Beyond personal memoirs, it seems the writers were aiming at capturing the essence of the times. And the same goes for the stories from Nigeria and Cameroon, some of the stories were expertly crafted miniatures.

- Poet's corner

Starting with the work of a young Lasana M. Sekou and later expanding considerably as readers felt the muse.

The masthead shows a long list of

contributors

Prompted by the lively letters column, the submissions came in fast.

Some correspondents initially just wrote letters but were then compelled or outraged by the content they read and came to submit their opinion pieces. Fondly for example,

Anis Haffar and the late

John Randall.

Tehtey was a striking correspondent at large.

Kodwo Mbir Bullard and

Colonel Annor Odjidja provoked debate.

J.H. Mensah in exile penned a few pieces as he attempted to marshall the Ghana Democratic Movement from exile.

A like minded soul also stepped up Kodjo Crobsen published

Power to the People, his biting satire of Ghana's history and would contribute the occasional cover and cartoon.

Towards the end,

Jo Mini started to send some of his cartoons.

Andrew Scott Stoker weighed in the weight of the Flight Lieutenant.

And for good measure you can also read a few speeches

Shehu Shagari just before he was ousted, a typically rambling

Rawlings, or a waffling

Kwesi Botchwey dancing around the IMF and World Bank policies he implemented.

"This weekly magazine which has been on the newstands from September 8, 1983 reports news and events and creates a forum for reasonable discussion of the problems of the West African region which are usually written off with simplistic explanations in western media."

- masthead on the back cover

Covering A Region in Turmoil, The Talking Drums Years

The history books talk of lost decades. The majority of living Africans are under the age of 18 and even those hitting adulthood this year will have known only the 1980s from their parents. Simply stated, the Eighties were a disastrous decade - more disastrous even than the Seventies. The early 80s were the nadir for most countries (modulo Rwanda, Zimbabwe and Congo); suffice to say that the Talking Drums years were trying times. Herewith, then, some notes on these troubled times and a timeline of sorts...

(sidenote:

1989 was the year that saw things begin to turn around in most of Africa but "in 1989 only three countries in Africa could claim to have democratic governments." The major damage was done earlier in the decade)

Of Strongmen in Suits, Military Men in Khaki and Rogues in Flowing Robes

The spectre of coups would lead the way but, before we get onto those army minded people, we can perhaps start with the more refined beasts that were laying waste to the continent.

The archive is full of priceless nuggets - take this one for example:

Gabon - Bongo defends one party system

The sixteenth anniversary of the founding of the Gabonese Democratic Party was marked last Wednesday with a speech by President Omar Bongo in which he once again justified the adoption of the one-party system. The first reason, according to Omar Bongo, was the unfortunate experience with the multiparty system in Gabon from 1960 to 1967 which accentuated tribalism, regionalism and clan division.

The second reason given by President Bongo was that the multiparty system is foreign; it belongs to the whites, therefore it is not adapted to or rather it is in opposition to the realities of African politics...

While I am President of this country, there will be no multiparty system.

He was certainly right about this, and he proceeded to suborn and corrupt even when forced by the donors into an ostensibly multiparty system in the nineties - complete with rigged elections. Omar Bongo died happily in power serving as president for almost 42 years. He was succeeded by his son who was carrying on in much the same vein until a recent palace coup.

The rulers that weren't ostensibly military were nevertheless authoritarian and didn't tolerate dissent. In many countries, there were one-party states or, at best, a simulacrum of democracy. Dissent was thoroughly and vigorously neutered. The Francophone operators were particularly smoooth operators -

Houphouët-Boigny and others reigned in a similar manner.

Siaka Stevens of Sierra Leone saw no reason to divert from this vulture trend perhaps setting the stage for the country's descent in the 90s.

A Company of Coup Makers

Coups are inherently unstable affairs as seizing power often involves the use of force. Even for the more efficient coups, the threat of force comes with the territory. Once in powere, one needs to stamp out any signs of dissent lest the unnatural situation one has placed the country in be seen as intolerable. Blood is spilled as a matter of course by the various groups that are jostling for power. An era of coups is full of random and arbitrary violence, oppression of the populace, suppression of dissent, intolerance of criticism and vendettas pursued without restraint.

A priori coup makers start with conspiracy in mind and their mindset is full of conspiratorial lore, they are prone to plots and the thin-skinned among the cabal are wary of losing their place (and perhaps their life). Falling out among the members of the cabal is not unknown. Violence then is pervasive even in the most disciplined. The coup drill is well known, ban on political parties, dissolution of any pesky institutions or norms, troublesome constitutions, nagging judiciary and so forth. Journalists should be stenographers repeating your latest utterances. If you have an agenda - and some of most prominent in this age thought of themselves as revolutionaries, you are throwing a society into upheaval and should expect resistance.

And threats can be both internal and external. Your opposition may have relocated across the border. To clamp down you would often resort to

border closures. The 80s would be full of such dislocation with the consequent effect on trade and normal migration. Sometimes too, the rulers would resort to expulsions of foreigners mostly as scapegoats and threats to your country. Sabre-ratting with your neighbors was all too common. If you were Sekou Toure of Guinea your legacy would be your increasingly brutal reaction to a

series of plots. Late, unlamented in his passing.

The Ghanaian coup makers, the Rawlings-Tsikata lot were not scared of blood and indeed welcomed it. To read the pages of Talking Drums is to take in the minutia of their project. Public tribunals dispensing revolutionary justice, soldiers on a rampage delivering arbitrary justice, market women targeted and shaked down, curious ideas about land ownership laws, closure of newspapers and the list goes on. There was resistance albeit with a culture of silence but there was resistance nonetheless. More importantly, the background of violence never really stopped, one keeps reading about disappearances, beatings and torture almost every week.

The report on the judges's murders had been released confirming that the new regime were deeply implicated.

But the melody lingers on and many other articles covered the continuing atrocities and impunity of the very violent cabal that was determined to cleanse and conquer the country bringing their confused vision of marxist utopia.

Ghana had been living under a curfew since the coup and curfew was only lifted after two and a half years. (sidenote: the curfew destroyed all nightlife and it has taken decades to recover. Burger-Highlife came into being as musicians went into exile. John Collins has noted that the PNDC's imposition of a luxury goods tax of 160% on musical equipment changed the very instrumentation of that music, enter the Casio keyboard)

Many

journalists were detained, including

John Kugblenu, Mike Adjei, and Tommy Thompson the proprietor and Managing Director of the Free Press. The former two spent

a year in detention without charge.

Reports from Accra indicate that the two are in reasonable health considering the one year ordeal but those who have seen Mike Adjei say that he is half his normal size.

John Kugblenu died just two months after that release.

Tommy Thompson was a guest of the authorities a

number of times

And these were the luckier ones...

Kankam da Costa, former deputy defence minister in the Limann administration, was only freed after 4 years of detention without charges and then only on medical grounds (read: he too was near death).

A typical

intervention

Under a new law enacted by the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) in Accra, on August 30, offences involving the diversion of petroleum products and drugs will carry the sentence of death by a firing squad.

Diversion of goods, including food items, earmarked for educational institutions, hospitals and the general public will also carry the same sentence.

The

May 1985 column on Ghana must go decried the hazardous exodus from Lagos, but noted also

on its cover Ghana being carried out on a coffin with the comment "victim of the war declared on the economy by General Acheampong".

Sad as it may be, the PNDC were not the only violent actors.

Intercommunal fighting between Mamprusis and Kusasis broke out

in Bawku. The army wasn't felt to be neutral and could barely put a lid on the

bloody conflict that contines to echo to this day.

Ghana's

Catholic Bishops would call for representative government - this was in 1984 when people were still being routinely disappeared. The churches were the sole voluble opposition - indeed the only tolerated civil institution since political parties were banned. (sidenote: the universities were closed down for years at a time when students demonstrated against the regime)

This of course prompted vitriol - Rawlings would have many a foul-mouthed

outburst against Bishop Sarpong and others he felt slighted by. There was a lot of "who will rid me of this priest?" rhetoric. Indeed a Catholic priest would be murdered in short order just to let people know what was what. And that was that, our truth and reconciliation committee had their work cut out; a lot of blood was shed on Rawlings' watch.

Thomas Sankara had been installed into power in Upper Volta by Compaoré's unit in August 1983. He would eventually acknowledge the main backers of that effort: Libya and Ghana. It turned out that Rawlings had

exported his coup to Upper Volta. Not for nothing,

June 4th was

declared a public holiday "throughout the country, to enable the people to commemorate with joy this historic event along with the Ghanaian people".

The country was soon renamed to Burkina Faso. Sankara is much feted for personal probity and his drive against corruption and imperialism etc. but a number of the various social changes he tried to impose were resisted vigorously by civil society. Take his decree on the

abolition of individual land ownership. Protests would ensue.

He was also quite capricious, for example sending almost his entire cabinet to work on farms (other than a few, including a name who we first read about, Blaise Compaoré - who would later liquidate him - perhaps he wanted to preempt being banished to the farm on a whim)

In Liberia, the erstwhile Master Sergent and now Doctor Samuel Kanyon Doe was particularly paranoid, finding real and imagined plots all around him. To be a vice president or deputy of some sort under him was to live a tenuous life, precarity would be your closest companion.

As he was prompted by Ronald Reagan and company to make nice, he made it very clear to the rest of the country what would happen if you tried to form a party and run against him. Jail and a beating were the lesser fates for many would-be rivals. Dr

Amos Sawyer would

repeatedly face arrest and detention.

The poor academic. For good measure, the University of Liberia was

closed down following student demonstrations for months on end.

Statements were ominous even when Doe tried to

make nice

Meanwhile, the government has announced that Dr Amos Sawyer is not a wanted person and therefore should not be molested by soldiers or security men. According to an Information Ministry release, anyone violating this order will be seriously punished.

He would issue a dire

warning against socialists

Dr. Doe said Liberia would never become a breeding ground for socialism. He also warned parents, teachers and students against the evils of a socialist form of government. He said all those with the idea of socialism would not live to tell the story. This is the second same warning against socialism in a week. He said the PRC appreciated the support by students and teachers, but it would never allow anyone to bring misery to Liberians by bringing socialism to the country.

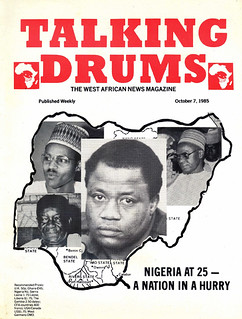

And then there's the case of Nigeria,

Shehu Shagari had won a second term and Nigeria was standing out as a beacon in tdhe region on the eve of the Buhari coup. Said coup was calamitous and the military intervention was a traumatic upheaval plunging Nigeria firmly into turmoil. Nigeria's military really put their countrymen through the wringer. Indiscipline was said to be the enemy and so a war was waged. All manner of outrages were visited on the populace: public whippings, beatings. Beyond this vague notion of corruption and indiscipline, the junta didn't really have any grand ideas or program to put forth save the

abolition of private universities. They just wanted to be the ones who dispensed the loot in the country

Buhari's so called war against indiscipline was exacting. Retroactive decrees were passed when the judiciary were not being complaisant. More decrees were passed when the once boisterous press wrote questioning articles.

The soldiers were fully unleashed on civil society. Maj-Gen Tunde Idiagbon, Buhari's right hand man, was a particularly

bloodthirsty leader

The other day, the Sunday Concord published a very startling story. It quoted authoritative sources as stating that an order had gone out to all police commissioners in Nigeria to arrange the execution of 828 condemned persons on death row within two weeks.

The order for the nationwide executions was said by the paper to have been given by the Chief of Staff Supreme Headquarters Maj-Gen Tunde Idiagbon just before he left for the funeral of the assassinated Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

Again, as in Ghana, the military leaders did not have the monopoly of violence. The

Maitatsine that had been relatively quiescent

broke out into

fiercesome rioting. The over-the-top reaction of the soldiers to the

religious movement would provoke a

disaster in Gombe in 1985. The seeds of Boko Haram were sown in what took place there.

Fela's

jail troubles were to be expected. The military rulers would not stand his kind of dissent, even if it came in the form of funky afrobeat.

Eventually a palace coup (long rumored) would take place and

Ibrahim Babangida would take over (the Buhari/Idiagbon combination was too toxic and bad for business)

Deliciously there was a

night of songs for Idiagbon when he was sent to prison - how the mighty fell

inmates were said to have held a night of songs for the deposed army chief.

The report said that although the prisoners did not rehearse the songs prior to the night, they were able to sing uniformly from their cells, such numbers as "no condition is permanent in this world, he who lives in a glass-house should not throw stones, life is like a boomerang, whatever goes up must come down."

Paul Biya would emerge shaken after a failed coup in Cameroon, evidence of how a coup could be resisted albeit with a big death toll. In surviving, he would never look back but he also didn't resist vindictiveness and the thrall of the

security services

Officially, 1,053 people were arrested in connection with the coup plot, 617 were freed immediately, 436 cases were heard by a military court, 46 death sentences were passed, three in absentia, two sentence of life imprisonment, 183 received prison terms of between two and 20 years, another 183 were freed while 22 had their cases referred for further investigation.

He would confidently say a year later that Cameroon was a

land of plenty and he has certainly enjoyed plenty of what it has to give - he remains in power to this day.

Suffice to say that military-civilian relations were universally poor throughout the continent. Or if you want a graphical illustration of what was in the zeitgest, here's a word frequency visualization of a region in turmoil.

Simply consider the consecutive headline stories one week in Ghana:

June 3 1985, Note: this is a full three and a half years after the PNDC came to power

- 2 majors executed

- 3 executed for fraud

- 4 sentenced to death

- Links with dissident - six to die

- More death sentences

As a later article would put it Africa was a

land of political volcanoes

Natural and Man-Made Disasters

Against this political backdrop, nature also worsened things considerably bringing the most dramatic drought in the region in 40 years. 1982 to 1985 were tough years in most parts of Africa. Bush fires all over the Sahel caused crops to be destroyed. Food emergencies would be the order of the day even without governments who were actively sabotaging the basis of their economies in the name of a revolutionary reshaping of their society.

The food crisis was pervasive on the continent and at its worst in Ethiopia, famine was rampant as predicted, we saw the callous indifference of the government.

As well as the images that roused

Band Aid,

Live Aid and other charitable relief efforts -

Bob Geldof (who would be satirized in these pages)

Structural Adjustment

There was almost too much history in 1980s Africa. Beyond the backdrop of drought and famine the violence and political turmoil, the economic upheaval was also significant. Some might say that the economic distress did as much violence to Africans. What was pitched and experimented on many countries was later rebranded as "Structural Adjustment with a human face". The implication, then, of what became known as the Washington consensus is that what African countries faced in the 80s was the raw, unvarnished, cold blooded treatment.

Many countries had to negotiate debts incurred in the 70s while dealing with failing crops and political change. A certain amount of hypocrisy govens the dealings of the IMF and World Bank with African states for the former were reliant on authoritarian governments unaccountable to parliaments and willing to run roughshod over their populace's interests.

Many regimes would dictate half baked policies and force through onerous burdens on their countries. the countries that were in distress were often not even really negotiating with the donors - Africans who working in the IMF and World Bank would implore the Finance ministers to come prepared and at least argue for better terms. In many cases, however the countries would simply accept wholesale the trial balloon they were pitched.

Ghana would undergo "the

steepest overnight currency devaluation in recorded history". Certainly the steepest devaluation since the IMF's founding was an overnight shock to the system.

Cote d'Ivoire and Nigeria would also face similar devaluation and debasing of their economy, opening. True the various regimes didn't help but the human toll was severe. Sample headline that would follow

Porter dies in bank queue waiting to withdraw money for two days.

There would be many articles quietly observing the effect of devaluation and deprivation, a kind of inflation calypso in

day to day life

After a while, no explanations were asked or given, a little sad and knowing glance, muted tones "how much?...... Five? Okay, I'll see what I can do. Will you take four?. Please make it four and a half".

Transaction concluded. For each figure mentioned, simply add a thousand, Ghanaians had become so embarrassed by the worthlessness of their currency, they do not bother to add things like tens, or hundreds any more, if you ask for the price of something and you are told "five" do not make the mistake and think the price is five cedis; "five" is understood as "five thousand cedis". It is this practice of selling personal goods that has come to be known as "affect".

Greater Africa

The OAU was a dysfunctional

mess to say the least. The only point of consensus was on the revulsion against the South African apartheid regime (its dire policies inside the country and the repeated raids into neighbouring Angola, Mozambique and Lesotho) and the anti-colonial struggle in Namibia. Thus,

Cuban assistance was welcomed. Mrs Thatcher and Ronald Reagan's supportive stances on apartheid and against sanctions were duly savaged by all parties.

Pik Botha's visit to London was denounced. The anti-colonial message drew countries together but it was a case of see no evil when neighbors were oppressing their own people - so long as the damage was contained within borders no leader complained

Unanimity was lacking in other areas, the once formidable boycott of Israel was breeched. Liberia would

resume relations and then Nigeria's new military rules would

collaborate in clandestine ways with the Israelis (the money was too good to pass). Morocco

threatened, and then

pulled out of the OAU over the Western Sahara issue.

Eyadema, the prince of darkness himself, is the emblem of diplomacy and acts as an elder statesman

leading negotiations over Chad

"You also know of the proverb which says that when a wall has no crack, lizards cannot enter through it in the evening. The wall, at the moment, has a crack. What I mean is that the intervention of foreign forces today is a result of the leaders' differences.”

A similarly bloodthirsty Colonel Mengistu who never shied from confrontation was made chairman of the OAU and meant to lead negotiations over the conflicts in Chad and Western Sahara and bring peace those areas.

Colonel Gaddafi had previously been OAU chairman but was not a disinterested party as he was

propping up one of the sides in the Chad conflict. The

French intervened on the other side.

Gaddafi of course supported the coups in Ghana and Upper Volta and was exporting his

Green Book ideology across the continent as he would do until his death. Green Book study groups would meet in many countries.

Guy Penne of France

visiting his

client states. If Francafrique was not his creation, he worked hard to ensure its smooth running, the circle of patronage and back scratching between Paris and the dicatator's club was complete.

In Uganda,

Yoweri Museveni's guerillas were battling with the troops of General Tito Okello, their civil war. By the end of the magazine's run in 1986, Museveni had won. Talking Drums would

continue to warn about the

traps that lay ahead that military men often fall into. Decades later, Museveni continues to rule - power corrupting the men in khaki as it almost always does.

At the same time, there were signs that the culture of silence in Ghana and Nigeria was cracking - the students had turned against the regimes with big demonstrations against the depredatory IMF and World Bank structural adjustment programs that had been imposed;

Paa Willie's lecture series at the Danquah institute.

In the foregoing, I have picked out a few obvious threads but there are many others that can be woven in the archive. Beyond the heavy political writing, there is much of note in the cultural realm. Any issue has food for thought, consider reflections on the US

invasion of Grenada Operation Urgent Fury,

waking up to disaster IRA bombs in Brighton, whether

Ghana and Poland were poles apart or correspondents asking whether

Desmond Tutu should reject his Nobel Prize or try tracing later names of interest, Abacha, Abiola, Compaoré etc. or say perceptions of AIDS - then viewed as a first world disease. Or read some short stories and columns, there's something for everyone in those pages.

I welcome your own readings.

Creating the Archive

It is fair to say that Talking Drums was a family affair. My first job, as it were, as a teenager was helping my mother and her colleagues label envelopes and stuff magazines in them to mail out our weekly subscriptions. I spent my summers in what passed for a newsroom at Madhav House, soaking in the atmosphere as news developed, taking calls with stringers asking them when they were planning to send their reports, proof reading and editing copy and occasionally helping shape the articles that would be conjured up just before deadline. I always marveled at how the issue would materialize in those few hours before we would go to press.

The magazine punched above its weight, was widely read and influential, albeit run on a shoestring budget. Its biggest impact was in telling an alternate story of Africa for those four years. It kept those others, the West Africa magazines and the Jeune Afriques of the world on their toes. Western pundits that would normally blowviate in the pages of The Guardian, Times or Telegraph would pause before glossing and delivering their bromides - everyone was on notice. The energy of the journalists involved amazed me at the time and I trust you'll find lots to savor as you browse the issues.

The archive, such as it was, had been sitting in my mother's garage, having made its way from London to Accra sought out by researchers almost to no avail. Back in 2011, I scanned the

covers as a first step to digitize the magazine when I came across them in our garage. The covers alone told a tale.

Occasionally since, I'd scan a few articles to illustrate some point. Then, prompted by the pandemic, I finally decided to help rescue the rest to bring it to the web. For a few hours in the afternoon before I would catch a flight back to my current home in Texas, I simply took photos with my camera of as many pages of the magazines that I could find. I found that to be more expeditious, if less professional, than using a scanner.

My next tool was Google Lens to extract the text from the 2,500 odd images which I then used to manually craft this web site - hand writing the html with a trusty text editor. Blame any errors on my lack of photographic prowess and my poor man's toolchain. Similarly the design aesthetic is by necessity low brow, the writing is what I thought mattered.

Some statistics: I came across 99 issues in my endeavors but, for a few issues, I only seem have photographed a few pages besides the cover. I will try to fill in the rest if possible when I next get to the hard copies. I believe Stanford may have some

copies - judging by what is on

Google Books. If you manage to find any additional issues, I'd be grateful to add to the collection.

I'll let the search engines archive things and add a search page to augment my poor man's indexing. Do let me know if you spot any cobwebs on the site.

I've started to flesh out a few features to highlight a few interesting topics, the first: we're coming up to the 40th anniversay of the

Umaru Dikko affair. I hope to add a few more. This being said, I believe there is grand body of work that deserves a wider audience.

Forty years on, Ben Mensah effortlessly recounted the vision that guided those that created Talking Drums:

We said there was a need for visionary leaders... we said there was a need for an informed public... And there was a need for critics as well. Because the work of dissenting is also a serious business. That came to be our motto.

Words to live by and a manifesto of sorts.

Welcome to

Talking Drums.

File under: journalism, media, archive, news, politics, history, Ghana, Nigeria, Africa, culture, observation, perception, dissent, coup, military, England, Talking Drums, magazine, Observers are worried, toli